It is with great sadness that G4G notes the death of longtime G4G community member Robert Abbott (Mar 2, 1933 – Feb 20, 2018) from the USA.

G4G14 Eleusis Express Tournament

Announcement: The 14th Gathering 4 Gardner conference will feature a tribute Eleusis Express Tournament. Come join the fun, the mystery, and the challenge of playing a variation of Robert Abbott’s card game Eleusis! (pronounced el-you-sis) Featured in the Martin Gardner Mathematical Games columns of the June 1959 and of the October 1977 Scientific American. We’ll play Eleusis Express, a quick-play adaptation approved by Robert, led by John Golden (the adapter).

The Life of Robert Abbott

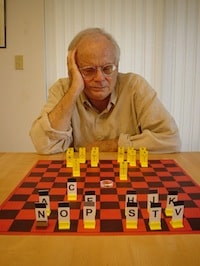

“Robert Abbott, an American game inventor, is remembered by his fans as ‘The Official Grand Old Man of Card Games’ ”.[1][15] He is also remembered for inventing creative board games, an equipment game, and logic mazes. “Auction was Abbott’s personal favorite card game”.[2] “Confusion was his favorite board game. Among his most famous logic maze creations are the Theseus and the Minotaur set of mazes which have recently been implemented on the iPhone and iPod”.[1]

Mr. Abbott died on February 20, 2018.

Cliff Saxton St. Louis Country Day School (CDS) ’64 and Larry Day ’51 wrote: “Bob Abbott has never been fond of following the path well-traveled, whether at Country Day or in his later professional life. Instead, his fascination with exploring the mysteries and meanderings of old rights-of-way—highways, railroads, trolley lines, or canals—was instrumental in his becoming the successful inventor, first, of card games, and then of mazes with specific rules that challenge the mind and encourage players’ own creativity. Abbott’s interest in game design is a pursuit he says was rooted in puzzles represented by plane geometry homework at Country Day.”[1]

Abbott said: “One principle I’ve always followed is, if I like a certain art form, then I try to create something in that form.”[4]

Robert wrote: “In my own experience, I found that my most creative periods were when I was paired with someone else. And there were a lot of someone elses in my life.”[4]

Robert Abbott was born on March 2, 1933 in St. Louis, Missouri.

“He began inventing games when he was fourteen and recruited his little sister, Margie, as a play tester.”[3] Robert said: “I also liked classical music when I was young, so I wrote one piano piece.”[4]

Abbott attended St. Louis Country Day (CDS) School.[4] “At CDS, his principal interest was practicing creative writing for The Codasco yearbook, and he served as co-feature editor of the weekly student newspaper, The News.”[1] “His best friend at Country Day was Bill Smart and they were a creative pair and they wrote humorous articles for the school newspaper.”[4] Robert Abbott wrote: “In high school, I invented an electric brain to play the game Nim. I made it out of the parts of only two pin-ball machines.”[7]

“Robert went to Yale for two years and then to the University of Colorado for another two years. His mathematical education was analytical geometry, logic, and Boolean algebra. One of his main interests was in the philosophy of science and the various modern schools of epistemology.”[7]

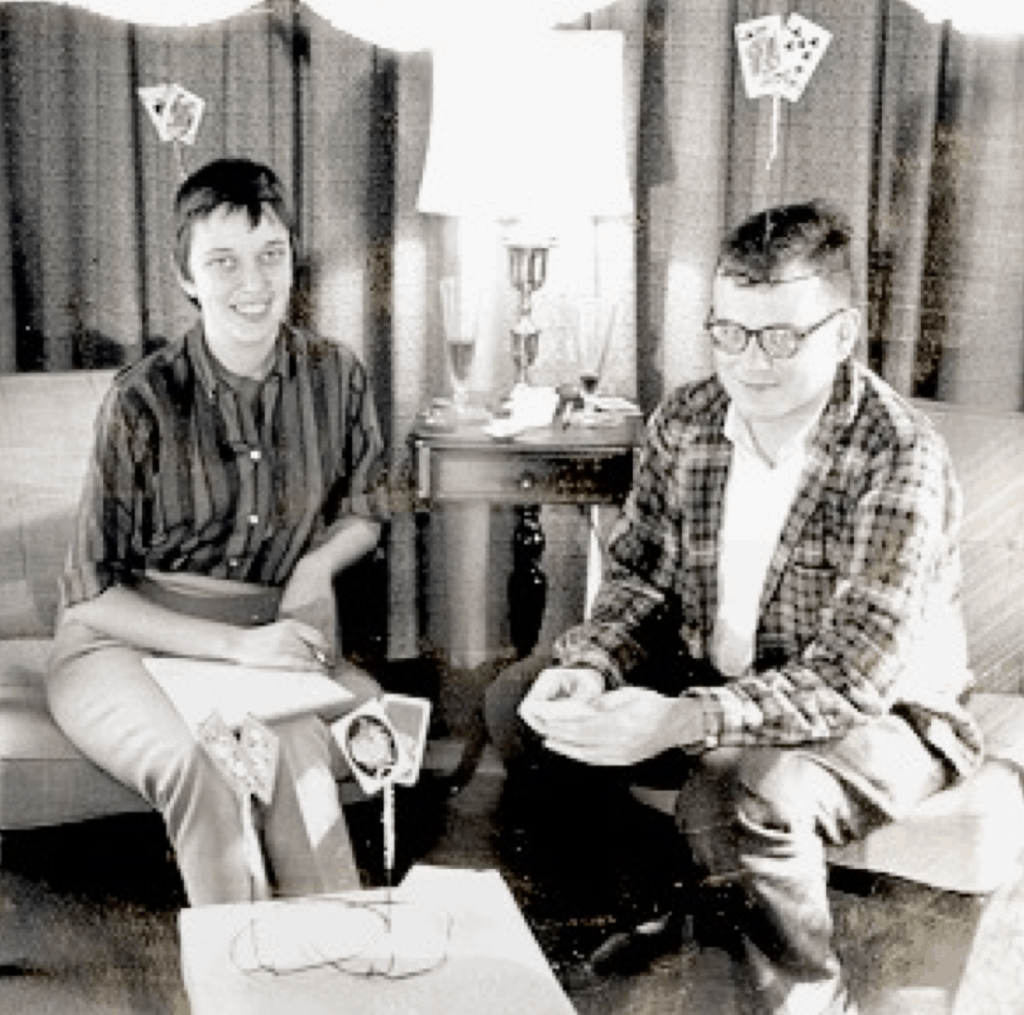

“His next creative pairing was with his first wife, Barbara. They met at the University of Colorado.”[4] “During this time (the 1950s) is when he created all of his card games, starting with Babel in 1951, and ending with Auction in 1956.”[15] Abbott invented the card game Eleusis (pronounced el-yu-sis) in 1956.[2][9] “For about two years, Barbara was a play-tester for these games. Eventually they broke up.”[4]

“Abbott next moved to New York City, where he worked at various clerk jobs.”[3]

On March 8, 1959, he wrote to Martin Gardner (who wrote the Mathematical Games column in Scientific American magazine) about his card game Eleusis, a game that uses inductive logic. He explained the rules.[5] In a March 22, 1959 letter to Mr. Gardner, Mr. Abbott wrote: “Game inventing is something I look at as a good means of self-expression… My idea for Eleusis came from reading an experiment on concept-formation.”[7]

Abbott said: “Games are the highest art form.” [9] He wrote: “I hope someday to write about games as an art. I have in the works a long series of essays on the principle of game design.” [9]

Martin Gardner wrote about Eleusis in the June 1959 Mathematical Games column in Scientific American.[8] It was subtitled in Scientific American as “the game that simulates the search for truth.” The goal of Eleusis is the discovery of a secret rule by which the very game is played, thus enabling its uncoverer to dispose successfully of all the cards on hand.”[9] “This was a life-changing experience for Abbott.”[3] “He was ‘discovered’ and encouraged by Martin Gardner.”[1]

Robert Abbott said: “I should say that I wouldn’t have gotten anywhere if Martin Gardner had not discovered me. In 1959 I sent him a letter about my card game Eleusis. This letter was from a complete unknown, someone with no publications or academic credentials. The majority of editors and the majority of writers wouldn’t have even read my letter. Martin not only read my letter, but he saw what was good about Eleusis. I had mentioned that the game involved inductive reasoning, but Martin also saw that the game could be an analogy for the scientific method. He devoted his next Scientific American column to Eleusis, and the game became quite popular.”[6]

“Eleusis subsequently appeared in Gardner’s The 2nd Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions.”[2]

“Abbott put together four of his card games, Babel, Eleusis, Leopard, and Construction, and privately published the book Four New Card Games, in 1962. The publisher Sol Stein had Abbott expand his book to eight card games (adding Auction, Variety, Metamorphosis, and Switch) plus one chess variant, called Ultima or Baroque chess, invented by Abbott. In 1963, this book was published by Stein and Day, as Abbott’s New Card Games. In 1968, there was a paperback edition published by Funk & Wagnalls.”[3]

“In the 1970’s (1973-77), Robert Abbott made some major improvements to Eleusis, including the option for a player to become a Prophet, who makes the call of right or wrong when others play. This version, The New Eleusis, was published in the Scientific American in October 1977. The booklet Auction 2002 and Eleusis (2001) gives a fascinating account of the development of the game, as well as rules and advice on play. In 1977 Abbott privately published the rules to the game Eleusis in his booklet The New Eleusis. The reference books that include Eleusis all consider the 1977 version to be the standard version of the game, and they refer to it simply as Eleusis.”[2]

“In 2006, John Golden developed a streamlined version of the game, intended to assist elementary school teachers in explaining the scientific method to students. Abbott himself considered the variant a ‘great game’, and refers to it as Eleusis Express.”[12]

“In 2008, RBA Libros published a Spanish version of his book Abbott’s New Card Games, under the title Diez juegos que no se parecen a nada, which translates to ‘Ten games that do not resemble anything’. This version was not just a Spanish translation of the original, however; the most up-to-date rules for the various games were used; in addition, the rules for Eleusis Express and Confusion (a board game) were included.”[15]

“His card game Eleusis is in most of the standard reference books devoted to card games: Hoyle’s Rules of Games (2001), edited by Philip Morehead, Penguin Encyclopedia of Card Games (2000), edited by David Parlett, Bicycle Official Rules of Card Games (1999), edited by Joli Kansil and Tom Braunlich, and New Rules for Classic Games (1992), by Wayne Schmitt-berger.”[2]

“Abbott considers Eleusis to be his greatest achievement.”[6]

“In 1963 Abbott wasn’t making much money. He decided to go back to St. Louis, where his brother-in-law, Bob Ellis, helped him get a job as a computer programmer at the Washington University Computer Research Laboratory. In 1965, Abbott moved back to New York, and for the next 20 years he continued to work as a programmer, mostly in IBM 360 assembly language.”[3] “The most fun he had was at the Bank of New York.”[6]

“It was at the Bank of New York, in 1974, that Bob met Ann. Ann graduated from Mt. Holyoke College with a BA in economics. At the Bank of New York, Ann and Abbott had a common interest in working on challenging computer applications. They were married in 1983.”[10]

“Abbott worked with IBM 360 assembler language and with teleprocessing, which was new at the time. He really enjoyed programming. At Bank of New York he worked with Peter Lawrence. He and Peter formed another creative pair. They essentially created their own programming language for creating screens on input devices and for processing the data entered. Their language was implemented using macros in the 360 assembler.”[4]

“While working at Bank of New York, he was still working with games. He became part of a games group that included Sid Sackson and Claude Soucie. He and Sid were another creative pair.”[4]

“Abbott invented the beautiful board game Epaminondas (also called Crossings), Ultima (also called Baroque chess), played with chess pieces on a regular checkerboard, and the board game Confusion.”[9] [17]

Abbott said: “Confusion is based on a pretty amazing concept: at the start of each game, you don’t know how any of your pieces move.”[14]

When Abbott was asked by W. Eric Martin: “How did Confusion originate?”[13]

Abbott answered: “Actually it started with an off-hand comment by a guy I worked with at Bank of New York. He said, ‘In your game Eleusis, you don’t know what cards can be played. Why don’t you make a board game where you don’t know how pieces move?’ I thought, ‘Of course!’ and I immediately started thinking about Confusion. The guy at Bank of New York was George Brancaccio, and I mention him in the original acknowledgements.” [13]

“Abbott initially created the game Confusion in the 1970s, and had it in finished form by 1980. The game was published in Germany by Franjos in 1992; Abbott was not satisfied with this version, however, due to several flaws in it. The rules were published in the Spanish translation of his book Abbott’s New Card Games in 2008, but the game did not get published in North America until 2011. This Stronghold Games version was named ‘Best New Abstract Strategy Game’ for 2012 by GAMES Magazine.”[15]

“Abbott invented the Equipment Game called What’s That on My Head? (known in Germany as Egghead).[9][17][21] It is a game which uses an informal logic to help players figure out which three cards are on a device on their heads.”[9]”

He first joined Mensa in the sixties. [9]

“It was Abbott’s passion for following something, like unexplained old rights-of-way, that spurred his interest in mazes. While at Country Day School, he led expeditions to explore the largely underground River Des Peres drainage canal. On Long Island, he found his most interesting ‘mystery’ right-of-way that turned out to be part of the 45-mile Long Island (Vanderbilt) Motor Parkway, the nation’s first ‘superhighway’ built in 1908.”[1]

After creating games, he designed logic mazes or mazes with rules.[1]

“Abbott is the inventor of a style of maze called logic mazes. A logic maze has a set of rules, ranging from the basic (such as ‘you cannot make left turns’) to the extremely complicated. These mazes are also called ‘Multi-State mazes’. The reason for this name is that sometimes you can return to a position you were in before, but be traveling in a different direction. That change in direction can put you in a different state and open up different choices for you. One example, from the book SuperMazes, would be a rolling-die maze. Where you can move from a particular square depends on what number is facing up on the die. If you return to that same square, the die may be in a different state, with a different number on top. Thus, you would have different options than the first time.”[15]

“Robert’s first logic maze and the first logic maze ever published, Traffic Maze in Floyd’s Knob, appeared in the October 1962 issue of Scientific American in Martin Gardner’s Mathematical Games column.”[15] “In 1990 a harder version of this maze under the name, The Farmer Goes to Market, was published in Robert Abbott’s book, Mad Mazes.”[18]

He wrote Mad Mazes in 1990 and SuperMazes in 1997. “Where are the Cows? is one of Abbott’s most difficult mazes. It first appeared in his book SuperMazes.”[15] Abbott warns readers that it “may be too difficult for anyone to solve.”[23]

“In 2010, his maze, Where are the Cows? was published by the Oxford University Press in the book Cows in the Maze, a book written by Ian Stewart.”[3]

“Theseus and the Minotaur is another of Abbott’s better-known mazes. It first appeared in his book Mad Mazes. Like Where are the Cows? in SuperMazes, Abbott says that this ‘is the hardest maze in the book; in fact, it is possible that no one will solve it.’ ”[15]

“Abbott and Andrea Gilbert are another creative pair, working with logic mazes.”[4]

Robert Abbott wrote: “I created The Bureaucratic Maze, something that doesn’t look like a maze at all. In it, you carry forms from desk to desk. The forms have information about what desk you came from and what choice you have of desks you can go to. When you arrive at a desk, the ‘bureaucrat’ at that desk gives you another form, and what form he gives you depends on what desk you just came from. Therefore, at any desk you are in different states, depending on which desk you came from. This is the same as the Colossal Cave: in any room you are in different states, depending on what room you came from.”[6]

Abbott’s Walk-Through Logic Mazes started with his 1993 idea. [19]

The opening of the first site was in 1998. [19]

Robert Abbott wrote: “The idea for these mazes (walk-through logic mazes) began in January 1993 when I was invited to participate in a puzzle exhibit at the Atlanta International Museum of Art and Design. The exhibit was dedicated to Martin Gardner, who wrote the Mathematical Games column in Scientific American. I was invited because Gardner had twice written about my game Eleusis and had printed two of my mazes.”

I designed a maze for the museum that was a grid of paths to walk on. There were twelve intersections where the paths crossed. As you approached an intersection you saw a sign on your right with one or more arrows. The arrows told you what turns you could make at the intersection—for example, you might see a sign with two arrows that indicate you can only go straight or turn left.” [19]

“Abbott’s walk-through mazes have been erected adjacent to the cornfield mazes.”[1]

“The first site to open was on July 4, 1998 at Tanglewood Park just west of Winston-Salem, North Carolina.”[19]

“Other walk-through mazes sites were Pacific Earth in Camarillo, California, Cherry Crest Farm near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Howell Living History Farm near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and Belvedere Plantation near Fredericksburg, Virginia.”[20]

Ann wrote: “In 1998 Bob’s walk-through mazes were added to cornfield maze locations and we made regular trips to see the implementations of the mazes on the east coast.”[10]

Abbott said: “The best compliments I have received have come from people who said they wanted to build similar mazes in their back yards. The mazes work for all ages – young children are happy to wander around among the hay bales, and their parents can also be in the maze attempting to discover the solution.” [1]

“Albert Morehead reviewed Abbott’s New Card Games in The New York Times on October 31, 1963.”[2] The review concluded with this paragraph: “Robert Abbott’s book is for lovers of the unfamiliar challenge, and historical precedent warns that Mr. Abbott may have to wait a few hundred years before his games yield glory to his memory.” [2] As Abbott said: ”Well, he was wrong. It only took about forty years!” [2]

This is a testament to Mr. Abbott’s ability to not only create brilliant and challenging games, but to also make them accessible and fun for others, either on paper, the computer, or with walk-through mazes!

Mr. Abbott was loved by his puzzle fans and by all who knew him. He was a pioneer in making creative card games, board games, and logic mazes. Because he questioned and challenged the conventional rules, he was able to create new fascinating games with new rules.

Just as he created the role of a Prophet in The New Eleusis, Mr. Abbott’s brilliant thinking, whether with card games, board games, or logic mazes, makes him a Prophet for the future of thinking games, and, more generally, thinking.

How fortunate we are to have witnessed the genius of Robert Abbott in our generation!

Cliff Saxton CDS ’64 and Larry Day ’51 wrote:

“Bob Abbott has never been fond of following the path well-traveled.”[1]

Paraphrasing Robert Frost:

Robert Abbott took the path less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference. [22]

“Abbott lived in Jupiter, Florida with his wife, Ann. There he concentrated on his website, www.logicmazes.com and used JavaScript to implement new mazes.”[1] Ann helped Abbott test his mazes before they were published.[16] “Bob and Ann used to do a lot of logic puzzles. They went through every issue of Dell Logic Puzzles.”[6]

Mr. Abbott is sorely missed.

Robert Abbott is survived by his wife Ann Abbott of Jupiter, Florida.

The author, Sandra Sharon, is deeply grateful to Ann Abbott for supplying invaluable information: correspondence, interviews Abbott gave, brief autobiographical sketches, interesting pictures, several phone interviews, and for answering all of her many questions.

The author thanks Ann Abbott for proofreading the final draft.

All the pictures are Courtesy of Ann Abbott.

The author thanks Nancy Blachman for giving her the honor of writing this obituary and for Nancy’s constant guidance and support during the whole process.

The author thanks Alice Peters for reading the final draft and for providing very helpful edits and suggestions.

List of Games, Mazes, and Books created by Robert Abbott [17]

Go to: www.logicmazes.com/games/

Robert Abbott created eight card games, four board games, one equipment game, and two logic maze (or mazes-with-rules) books.

The eight card games are Babel, Eleusis, Leopard, Construction, Auction, Variety, Metamorphosis, and Switch.

Babel, Eleusis, Leopard, and Construction were privately published, by Robert Abbott, in the book, Four New Card Games, in 1962.

The publisher Sol Stein had Abbott expand his book to eight card games (adding Auction, Variety, Metamorphosis, and Switch) plus one chess variant, called Ultima or Baroque chess, invented by Abbott. In 1963 this book was published by Stein and Day, as Abbott’s New Card Games. In 1968 there was a paperback edition published by Funk & Wagnalls.

Milton Bradley did an equipment version of Switch called High Hand.

The four board games are Confusion, Epaminondas (also called Crossings), Ultima (also called Baroque), played with chess pieces on a regular checkerboard, and High Hand.

The equipment game is What’s That on My Head? (known in Germany as Egghead).

Mr. Abbott wrote two logic maze (or mazes-with-rules) books: Mad Mazes and SuperMazes.

“Two of his mazes Theseus and the Minotaur and Where are the Cows? are considered by Abbott to be too difficult for anyone to solve.”[15],

Bibliography

- Saxton, Cliff (Fall 2008) “Simply A-MAZE-ing”, MICDS Class Notes, 16(2) p. 11

Editor’s Note. Special thanks to Larry Day ’51, who provided information for this article. - Abbott, Robert, Auction 2002 and Eleusis

- Wikipedia Draft 2011

- Autobiography by Abbott, Sept. 21, 2010

- Letter from Robert Abbott to Martin Gardner, March 8, 1959

- Robert Abbott interview from Puzzlemonster.com, November 2004

- Letter from Robert Abbott to Martin Gardner, March 22, 1959

- Gardner, Martin, The Colossal Book of Mathematics, page 504

- Buxbaum, David, MENSA BULLETIN May 1979, Number 226, A Genius for Games

- Ann Abbott bio

- Bob’s G4G7 Lecture on Axioms

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eleusis_(card_game) and http://www.logicmazes.com/games/eleusis/

- https://boardgamegeek.com/blogpost/2209/interview-robert-abbott-clears-air-about-confusion Interview: Robert Abbott Clears the Air about Confusion

- http://www.logicmazes.com/games/confusn.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Abbott_(game_designer)

- from a phone conversation with Ann Abbott

- http://www.logicmazes.com/games/

- http://www.ageofpuzzles.com/Masters/RobertAbbott/RobertAbbott.htm

- http://www.logicmazes.com/walkthru.html

- http://www.logicmazes.com/pics99x.html

- http://www.logicmazes.com/asdfgh.html

- https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44272/the-road-not-taken

- Pictures are Courtesy of Ann Abbott

“I first met Robert Abbott at G4G. Already at that time his fame had preceded him; as a devout devourer of Martin Gardner’s Scientific American collection books, I knew him as the inventor of Eleusis (probably the most scientific card game ever) and the writer of the book “Mad Mazes”. What I didn’t know at the time was that he was also a very kind and enthusiastic gentleman who could get very excited when I talked about using his inventions in other venues. Robert had invented a state maze he called the Bureaucratic Maze, where a solver had to go to different desks to get a paper signed. My insane idea was to actually use the Maze on an unsuspecting audience who didn’t realize that they were actually in a maze and not actual registration.

I actually did this twice for two separate puzzle events — the 7th Bay Area Night Game in 2005, and the other the Doctor When puzzle hunt in 2012. Bob was absolutely tickled pink when he learned that I had done so. Among those years, I also became more active in the board gaming community, when I learned that many of Bob’s games had become collector’s items due to their rarity — Code 777 and Confusion, both of which demanded high prices among collectors. (My two copies of High Hand, however, never appreciated much.) Of course, a high collectors value gives very little except name recognition to the original designer, so I am sure Bob was quite happy when both of those games were finally reprinted in the last decade and can now reach a new generation of players. A recent analysis on Board Game Geek placed Bob as the 5th most sought-after abstract game designer in the world. Bob was a master at finding ways to make deductive logic fun, both in his mazes and in his games. I’ll miss him.”

– Wei-Hwa Huang, onigame@gmail.com

Where can one obtain a copy of the latest rules for his card game Auction (2002) now that Mr. Abbott is no longer with us? Thank you.

Hi William,

Colm has attempted to get a response for you from the community via Twitter: https://twitter.com/WWMGT/status/1550832616223526915

Thanks,

Katie